Cutting Up An Ox (Part 2)

I hope you’ve taken some time to think about the difference between principle and technique as I discussed in part 1 of this series. Did you find the courage to set aside or better yet, dismantle your cherished techniques and discover the principle? If so, then bravo! That takes guts. Now you are ready to find the hidden space. What do I mean by “hidden space”? Let’s refer back to Zhuangzi’smasterful cook.

“Follows its own instinct

Guided by natural line,

By the secret opening,

The hidden space,

My cleaver finds its own way.

I cut through no joint, chop no bone.”

BE NEO

Once principle presides over technique, we see our work like Keanu Reeves’ character, Neo, who sees the hidden code behind the façade of the matrix. The rules and constraints of technique are now quite malleable.

Neo sees the underlying principle!

How do we apply our newfound superpower? Like Prince Wen’s cook, we find the hidden space. The space between the joints of the ox’s carcass is the metaphorical space that exists between all obstacles that we face. If we can’t see it, then we resist and struggle against the obstacles. We become like the cook who hacks through the bone wearing out both himself and his blade. Finding the hidden space allows us to act fluidly without resistance. Our energy is not wasted in fighting obstacles but adapting to them and reaching our goals with greater ease.

“There are spaces in the joints;

The blade is thin and keen:

When this thinness

Finds that space

There is all the room you need!”

The principle guides the technique and finds the space among the obstacles. Every apparent obstacle has its inherent space or opening around it. Allow the principle to guide you through that space. This space is actually the mental one within you that creates the solution. The mental space is created by not resisting what’s in front of you. Otherwise, you’re hacking through bone like the novice cook.

Create the mental space to see the opportunity int he obstacle.

When you’re faced with an obstacle, ask yourself three questions:

Is it really an obstacle?

Can I allow this to be just as it is?

How can I adapt to this?

Simply asking these questions begins to create the mental space necessary to find the path around the obstacle.

IS IT REALLY AN OBSTACLE?

Often, our existing beliefs and paradigms taint our perception of what’s in font of us. We size up people and circumstances based on our past experience rather than the present moment. “This is how I did it before”, “It’s always been this way”, or “This is not correct as I know it to be” are some of the limiting thoughts that can disguise an opportunity as an obstacle. We can reveal the “hidden space” when we observe without judgment. I can recall countless times in class where I’ve done a technique so often that I think I know it. This invariably backfires and the technique doesn’t work because the moment is unique and requires an equally unique response.

We often graft an old method or idea on a present condition because we perceive it to be the same or nearly the same. Even if this works to solve the immediate problem, it reinforces the habit of judgment and reactivity and diminishes our ability to respond authentically. We’ve shoehorned the square peg in the round hole. It got the job done, but at the expense of our awareness. To find the hidden space, we must see things for what they are, not what we think they are.

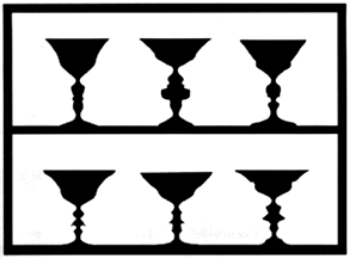

Do you see faces or vases?

CAN I ALLOW THIS TO BE JUST AS IT IS?

From a place of awareness, we can allow the situation to be whatever it is in the moment. By allowing, I’m not suggesting apathy or resignation. Both imply a retraction and a lack of engagement, which robs your energy, creativity and connection to life. You become a victim of circumstances rather than a master. When my opponents deliver a strike, I don’t cower or stand there and become a punching bag. But I also don’t resist them or ask them to change. Rather, I choose to accept it, and allow it to manifest however it may. Acceptance puts you in control. Rejection or resignation puts the control in the hands of another. If I cannot accept it, then I cannot change it.

“True, there are sometimes

Tough joints.

I feel them coming,

I slow down, I watch closely,

Hold back, barely move the blade,

And whump! the part falls away

Landing like a clod of earth.”

In Zhuangzi’s poem, the cook is fully aware of the joints that obstruct his blade. He doesn’t resist by hacking though them nor does he shy away. Imagine if the cook exclaimed, “This carcass has too many joints! My blade is getting dull and my arm is tired. I think I’ll find a new line of work.” In that case, the ox has cut him up instead!

Acceptance places us in a position of control where we can choose the most appropriate response. If our energy is spent rejecting something, then we just make it stronger and ourselves weaker. As an experiment, try punching a pillow. Hold it up with one hand and punch as hard as you can with the other. Don’t hold back. Give that darn pillow everything you’ve got! I know of someone who tried this and dislocated his shoulder. So, try at your own risk.

After a few devastating strikes, you may find your shoulder starting to hurt. No, you’re not a weakling, but rather the pillow is not resisting you! It completely accepts the full force of your punch with no resistance. It gives you nothing to fight against. Your own aggression pulls your humerus bone out of the shoulder joint. The pillow just accepts and remains in tact.

HOW CAN I ADAPT TO THIS?

Once we become aware and accepting of a situation, our response may not require nearly as much effort as we expected. It may even seem effortless. Much of our “effort” is normally put towards resisting rather than allowing and adapting. The cook barely moves the blade, yet the carcass falls apart almost on its own volition. This is Zhuangzi’s poetic way of saying, “Do less, achieve more.” Had the cook hacked his way through the bone, he’d being doing more and achieving less. You can also view the hidden space or the place of non-resistance as the 80/20 rule (Pareto Principle)- 80% of your results come from 20% of your efforts. The cook’s 20% effort is moving the blade between the joints. The 80% result is the “whump!” and the carcass falls apart.

Pareto Principle (aka “80/20 Rule”)

Adaptation implies an economy of energy. Resistance and struggle is wasted energy. The blade that hacks against the bone becomes dull and useless. Adaptation requires your full engagement with what’s in front of you. You neither resist, nor retreat but rather welcome it. The welcoming or allowing creates the opportunity to adapt, blend, flow and harmonize. From this place, solutions arise like the cook’s blade moving through the space between the joints- without resistance or struggle. My Tai Chi teacher always stresses the importance of borrowing your opponent’s energy in order to take their balance. “How can you borrow someone’s energy if you are resisting?” he’d ask. We can summarize the process as follows:

Awareness - > Allowance/Welcoming -> Adaptation -> Resolution

Adaptation is not manipulation or coercion. You’re not trying to trick, or deceive. Rather, you are changing and controlling yourself; the only thing you really can control. One of my Aikido teachers once said, “If you are trying to do something to someone, then you give them the option to say, ‘no’.”

Zhuangzi’s masterful cook has shown us the wisdom of following principle not technique and wielding it to discover the hidden space, the place of non-resistance amongst obstacles. I invite you to see where in your own life are you hacking through obstacles using worn out techniques that have become dull and ineffective. If your mind and body feel exhausted from the effort, then loosen your grip. Set aside the skill and embrace the underlying principle. Let the principle dictate the technique and become aware of the apparent obstacle. Create the hidden space in your mind by seeing it for what it is without judgment. Allow it. Welcome it. Borrow its energy. Adapt.

“Then I withdraw the blade,

I stand still

And let the joy of the work

Sink in.

I clean the blade

And put it away.”

Prince Wen Hui said,

”This is it! My cook has shown me

How I ought to live

My own life!””